Insurers are learning that the law was a Faustian bargain.

This Tuesday, Oct. 16, 2012, file photo, shows a portion of The UnitedHealth Group Inc.’s campus in Minnetonka, Minn. Photo: Associated Press

Updated Nov. 22, 2015 9:06 p.m. ET

Health insurance stocks took a nasty tumble last week, and maybe the markets are realizing that ObamaCare isn’t performing as well as the political class pretends. Sooner or later, reality tends to assert itself—for President Obama’s domestic legacy no less than his foreign policy.

The immediate cause of the selloff was UnitedHealth Group’s shock $425 million downgrade to its earnings forecast for 2015, almost entirely driven by losses on the Affordable Care Act exchanges. UnitedHealth is the largest U.S. insurer by enrollment, and the company is warning it may withdraw from ObamaCare in 2017. The insurer has already suspended advertising for its ObamaCare coverage and stopped paying commissions to insurance brokers for signing people up. It literally doesn’t want consumers to buy its products.

On a UnitedHealth call Thursday with Wall Street analysts, Josh Raskin of Barclays asked, “Simply, how long are you willing to lose money in exchanges?” and then followed up, “Are you willing to lose money again in 2017, Steve?” UnitedHealth CEO Stephen Hemsley replied: “No, we cannot sustain these losses. We can’t really subsidize a marketplace that doesn’t appear at the moment to be sustaining itself,” adding that “we saw no indication of anything actually improving.”

UnitedHealth reported one problem after another: An expensive risk pool that lacks the younger and healthier consumers who are supposed to buy overpriced plans to cross-subsidize everyone else. Enrollment growth continues to lag. People join the exchanges before they incur large medical expenses—insurers are required under ObamaCare to cover anyone who applies—and then drop out after they receive care. The collapse of the ObamaCare co-ops is recoiling through the market.

The reason the UnitedHealth disclosure jolted investors is that other insurers are almost certainly experiencing the same problems. Companies accountable to shareholders are not charities, and for all the new regulatory control that ObamaCare imposed on the industry, the government can’t force them to do business. (Not yet, anyway.) But the law is ever more obviously the Faustian bargain that we predicted and that insurers should have known better than to accept when they lobbied for the bill in 2009.

None of this means ObamaCare is rapidly “collapsing under its own weight,” as some Republican like to imagine. The entitlement will continue to trundle along, especially as it becomes ever more a vast Medicaid expansion. Commercial insurers are being displaced by Medicaid managed-care HMOs, with their ultra-narrow physician networks and closed drug formularies.

Then again, this trend is itself another symptom of decline. While liberals can continue to insist all is well, businesses don’t enjoy the same political luxury.

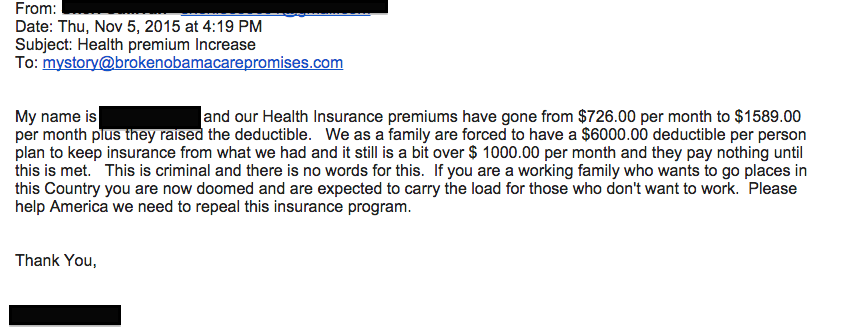

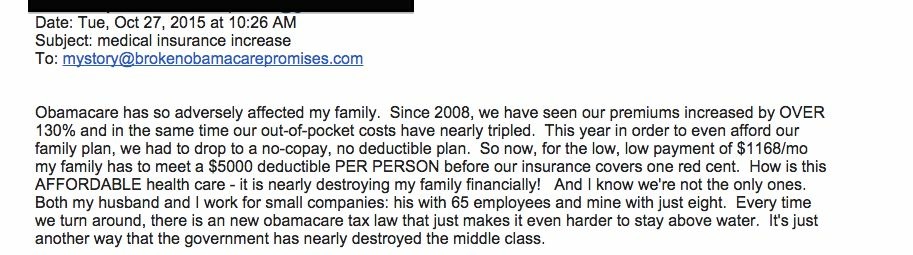

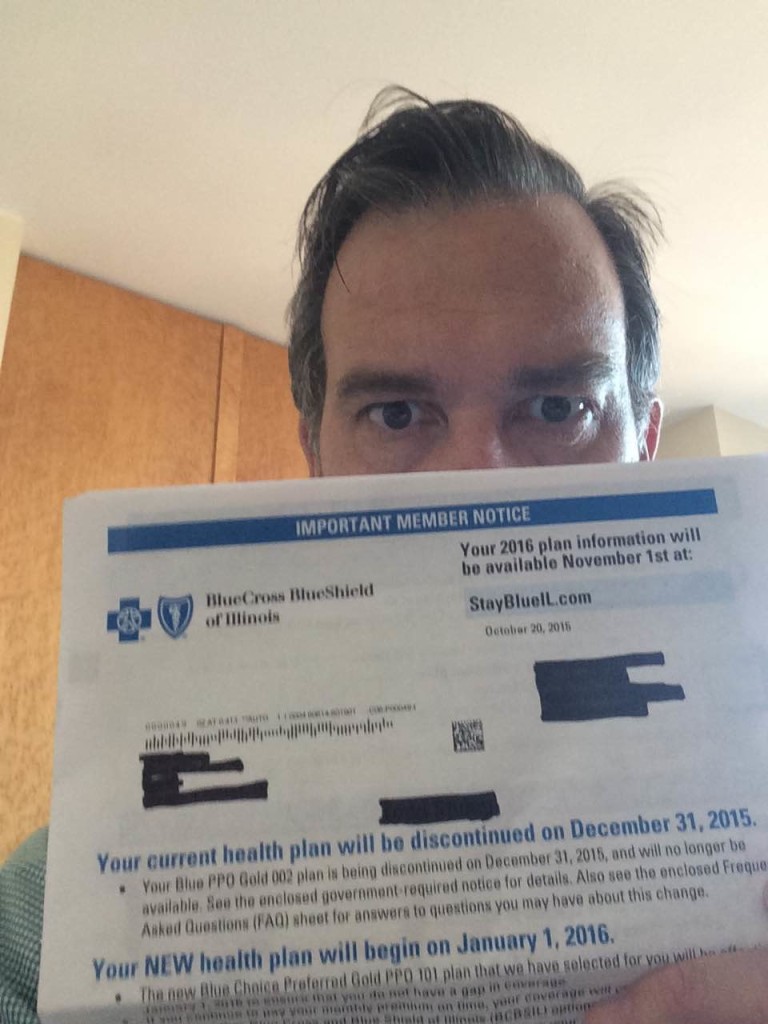

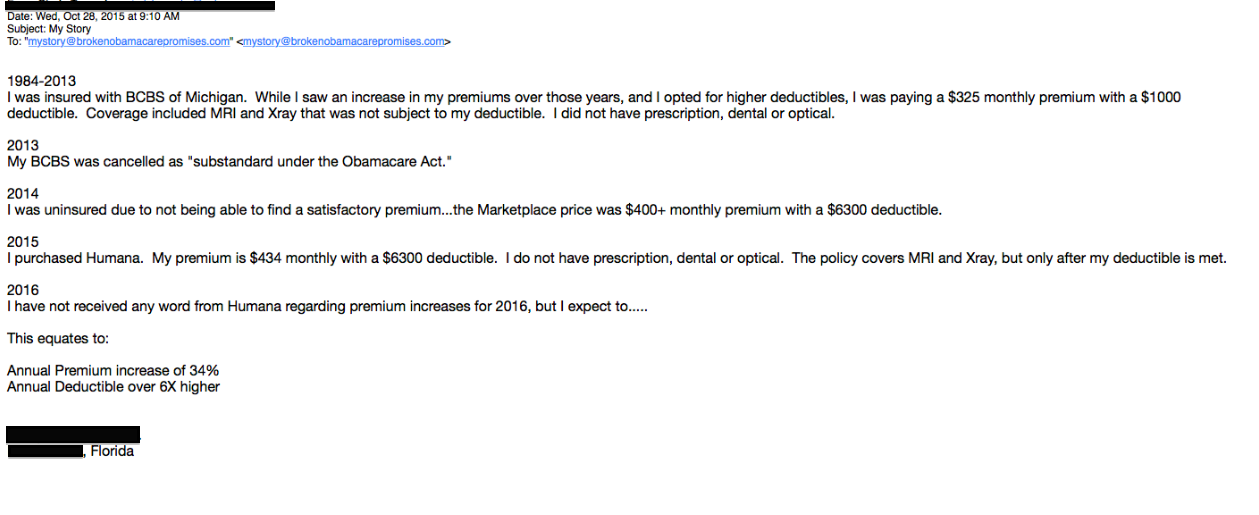

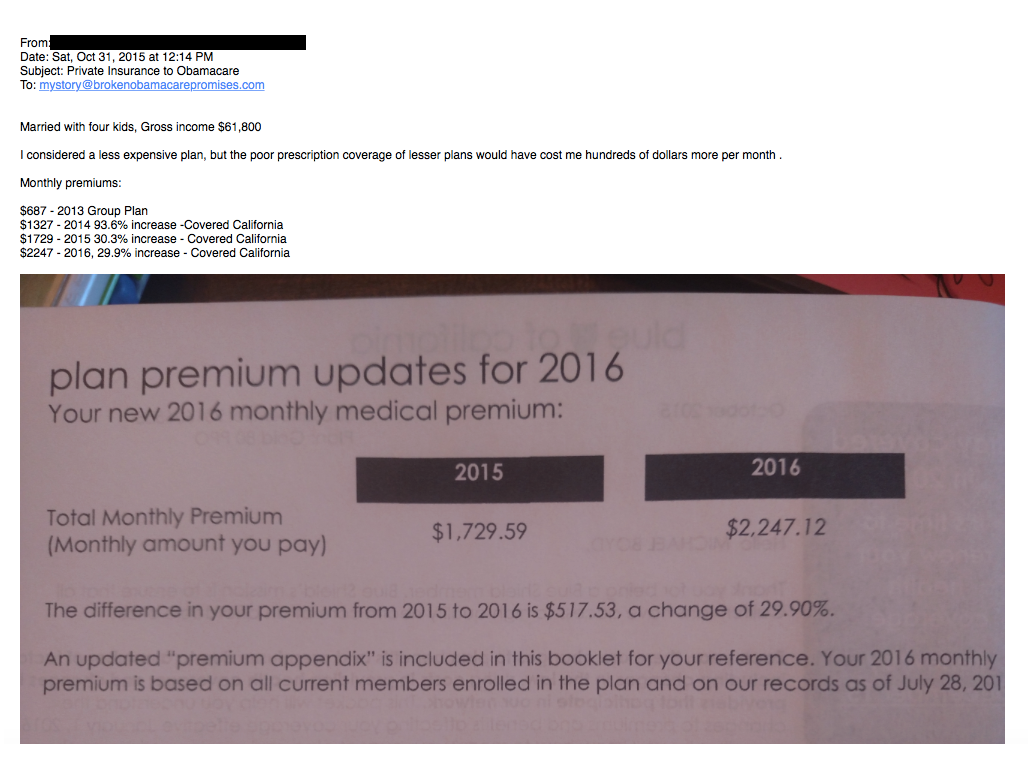

Note: Below is an example of someone who has to pay a higher increase in premium due to mandates imposed by Obamacare.